Research must be reliable and publication is part of our quality control system. Scientific articles get reviewed by peers and they get screened by editors. Reviewers ideally help improve the project and its presentation, and editors ideally select the best papers to publish.

Perhaps to help scientists through the sea of scholarly articles, an attempt has been made to quantify which journals are most important to read — and to publish in. This system — called impact factor — is used as a proxy for quality in decisions about hiring, grants, promotions, prizes and more. Unfortunately, that system is deeply flawed.

Impact factor is a scam. It should no longer be part of our quality control system.

What is impact factor?

A journal’s impact factor is assigned by Thomson Reuters, a private corporation, and is based on the listings they include in their annual Journal Citation Report.

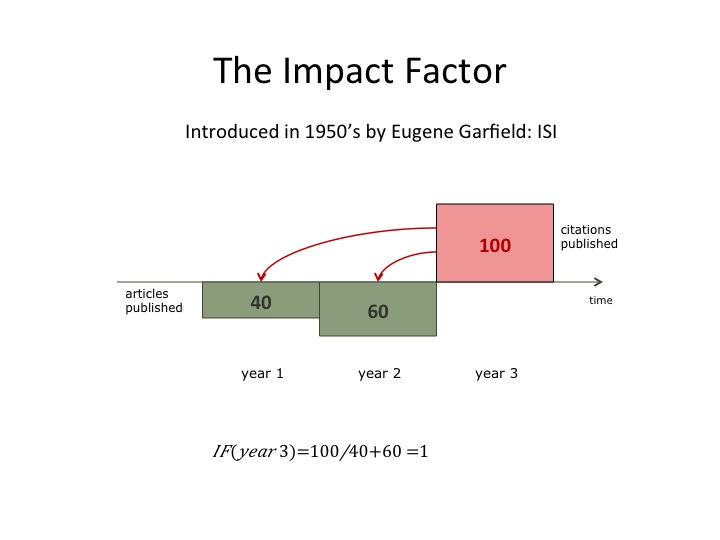

To calculate the impact factor for a journal in 2014 we have to know both the number of articles published in 2012 and 2013 and the number of citations those articles received in 2014; the latter is then divided by the former. If a journal publishes a total of 100 articles in 2012 and 2013, and if those articles collectively garner 100 citations in 2014, then the impact factor for 2014 is 1. Björn Brembs illustrates it like this.

Impact factor in the humanities

Impact factors in the natural sciences are much higher than those in the humanities. Journals in medicine or science can have impact factors as high as 50. In contrast, Language, the journal of the Linguistic Society of America, has an impact factor under 2 and many humanities journals are well under 1.

If impact factor indicates readership, this may be accurate. Journals in medicine or science may well have 50 times the readership of even the biggest humanities journals. But when impact factor accords prestige and even becomes a surrogate for quality, this variation can give the impression that the research performed in medicine and the sciences is of a higher quality or more important than the research performed in the humanities. I would wager that many political debates at universities are fed by such attitudes.

Fortunately, the explanation for low impact factors in the humanities is much simpler. While articles in top science journals often consist of a few pages, the ones in the humanities are more likely to be a few dozen. Naturally, it takes more time to review or revise a long article. As a result, many top journals in the humanities use 2-3 years from initial submission to publication. 2-3 years! This means that the window of measurement for impact factor calculation is often closed before a paper is even cited once.

What counts as an article?

Impact factor can be changed in two ways and both of them get gamed sometimes. One option is to increase the number of citations. Editors have been known to practice coercive citation, as I wrote about in How journals manipulate the importance of research and one way to fix it.

The second way to increase impact factors is to shrink the number of articles in the equation. In addition to articles, journals might include letters, opinion pieces, or replies. These are rarely cited, and sometimes editors have to negotiate with Thomson Reuters about which of them should be excluded from the count. The impact factor game provides an amusing description of this process.

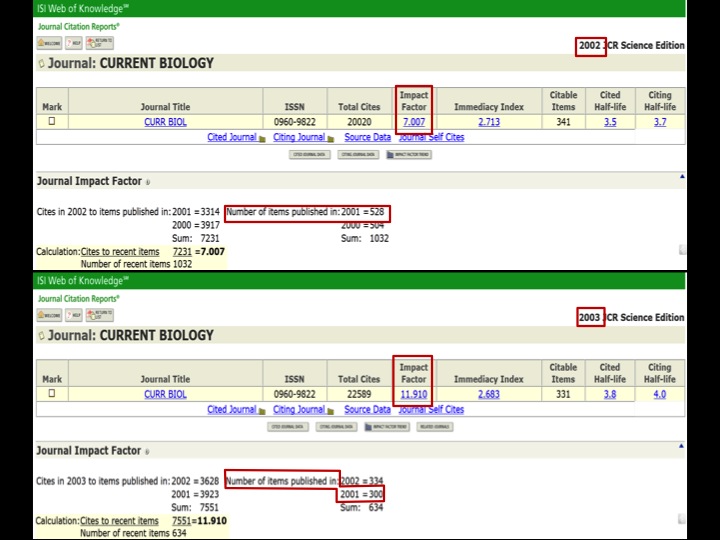

Current Biology saw its impact factor jump from 7 to almost 12 from 2002 to 2003. In a recent talk, Brembs reveals how this happened.

In the calculation of the impact factor for Current Biology in 2002, it was reported that the journal published 528 articles in 2001. But for the calculation in 2003 — for which 2001 is still relevant — that number had been reduced to 300. No wonder the impact factor took a hop! They can’t both be right and I wouldn’t be surprised if negotiations were involved.

We must build an infrastructure for research that delivers genuine quality control. Ad hoc windows that treat different fields differently and systems in which importance gets confounded with commercial interests cannot be part of this system.

And if we succeed in finding new ways to determine quality, impact factor will surely get bounced.

Many of the points in Brembs’ speech, When decade-old functionality would be progress: the desolate state of our scholarly infrastructure, deserve the attention of those who think about making scientific communication better; in addition to the slides, Brembs and his colleagues Katherine Button and Marcus Munafò have an important paper called Deep impact: unintended consequences of journal rank, which I’ve also discussed at The Guardian in Science research: 3 problems that point to a communications crisis. Brembs’ speech was made at the 2014 Munin Conference at the University of Tromsø.

Share

12 Comments

1 Trackback

Republish

I encourage you to republish this article online and in print, under the following conditions.

- You have to credit the author.

- If you’re republishing online, you must use our page view counter and link to its appearance here (included in the bottom of the HTML code), and include links from the story. In short, this means you should grab the html code below the post and use all of it.

- Unless otherwise noted, all my pieces here have a Creative Commons Attribution licence -- CC BY 4.0 -- and you must follow the (extremely minimal) conditions of that license.

- Keeping all this in mind, please take this work and spread it wherever it suits you to do so!

I find it interesting that the academic world is unable to create public awareness of the inadequacy of the rankings of this kind. It seems to be an increasing urge in poitics as well as press to keep counting and ranking, regardless of the connection between what you are measuring and counting (citings during two years) and what you want to know (quality of scientific journals). It does not require a PhD in anything to understand that this measure must be inadequate, yet as soon as it appears as a number in a table it becomes important for everything from funding to recruitment. What we need is proper scientific and methodical approaches to the quality of science in order to justify spending, nurture talent and bring humanity forward. What we have is counting of “easy to obtain, but insignificant” parameters. Where should we start?

This should be debated at high school levels in science, politics and law. Non bias investigators.

A couple of comments:

1. the issue of the time window is also one we see in science: some field simply move faster than others, and the window seems too short. There is also a five year impact factor, and there is a half life statistic that measures the rate of citation. It’s not obvious to me if a time free index is possible, but give me money for a PhD student and I’ll take a look!

2. The situation with Current Biology can be read in two ways. Their articles include short correspondences, a “Q&A”, and similar pieces, which are not “proper” articles, and thus most would agree that they shouldn’t be counted as research output. Presumably this was corrected by Thomson-Reuters in 2002 (and yes, presumaly because the publisher asked them about making the change). I don’t have a problem with this, as the alterntaive would be for Current Biology to cut out these sections that might be well read, but poorly cited. Where there is a problem is with transparency: the JIF is run by a private organisation. I sometimes wonder if it would be too difficult to use DOIs to create an alternative JIF, but I think human judgement would still be required to decide which articles should be included.

I don’t have more details about the Current Biology story, but there are more cases in the paper I cite by Brembs et al. My larger point about this is just the impact factor is in the technical sense unreliable. Attempts to calculate it by two different people will give two different results. The details of the Current Biology story would be one example of this and however “legitimate” they may be, they are nonetheless part of an irreproducible metric.

Hi Curt – to expand on our brief Twitter discussion: I agree that there may be some evidence that this particular proprietary manifestation of the concept of an impact factor is at best opaque and at worst potentially open to manipulation. Nonetheless, the concept of an impact factor is a useful one in many contexts.

We should not confuse the bibliographic concept (that the number of citations a journal receives divided by the number of papers it publishes over a similar time period can provide a useful comparative measure of the relative importance of siad journal when compared to others in its field) with a commercial product that employs the concept.

The title of your post suggests that using ‘impact factors’ in any way is a deceitful thing to do; I disagree, although you will find many academics who hold that position for ideological reasons, which is fine. If the title of your article were “JCR Impact Factors ™ are a scam”, I might be more inclined to agree with your premise (though not of course the potentially litigious wording thereof which is given here for entertainment and educational purposes only and in no way represents the author’s opinion on said product &c and so forth).

To repeat something I had to express in <100 characters: most people agree that spreadsheets are a good idea, but many people find MS Excel very difficult to use; most people would agree that a 'portable document format' that allows easy sharing of camera-ready copy is a good idea, but many find Adobe products most distasteful. This does not render spreadsheets and/or "pdfs" bad in and of themselves. The same should apply to the "impact factor", as opposed to the "Impact Factor". Let's not throw the baby out with the bathwater.

Hope that makes sense now. Cheers – Phil

Did you see the title of my post? “Quality control in research: the mysterious case of the bouncing impact factor”. Maybe someone else has given it a different title elsewhere?

Ouch. My bad. You need to look here:

http://t.co/yml2ppGOtv

‘ “IMPACT FACTOR IS A SCAM”, ARGUES CURT RICE ‘. The dangers of re-publication…

Another factor adding to the generally low IF for most humanities is the concept of «rural» versus «urban» research areas. If you research e.g. cancer, there are thousands of other researchers out there, who may cite your article. If you write about some obscure author, no-one else will research this specific topic and you won’t be cited. This has nothing to do with the merit of the articles, but of the size of the population of possible citers.

Right. And factors like that are natural enough. But given that rational explanation, it’s even more silly to use IF as a strategy for assessing quality between fields.

“This means that the window of measurement for impact factor calculation is often closed before a paper is even cited once”

wouldn’t the window of measurement open only after a paper has been published/after 2-3 years of review and revisions?

I can see that I may have been unclear in the way I formulated this. What I was trying to say is this: If I publish a paper in 2012 in Curt’s Journal, that paper can have consequences for the Impact Factor of Curt’s Journal in 2013 and 2014. To positively affect the Impact Factor, it must be cited. But if it appears in 2012, it’s unlikely that it will be cited in 2013 because anything that could reference that paper wouldn’t appear in print in 2013 and probably not in 2014, either. This is because the paper will first appear in 2012, then it has to have an influence on someone’s research, and then they have to write it up, jump through all the hoops to get it published and then it actually has to be published. In the humanities, which is what I was pointing to in the essay, because the time from submission to publication is so long, things are unlikely to appear at a point when they can have a positive effect on the IF, and the IFs of humanities journals are therefore — in part — much lower than IFs in science journals, where research papers are much shorter and more focused and published more quickly. In some fields, it’s considered slow if it takes 4 months from submission to publication. In the humanities, it could easily take 4 months from the time a reviewer receives and article until s/he starts even looking at it.

So, the window opens when the paper is published, but it closes before that paper could be cited in a leading journal in the humanities, given how slow the process is.

Yes, impact factor is completely a scam.